Lowndes - The Royal Mail

- The shades of evening were quickly spreading round us. As we came along I could almost fancy the form of Old Lowndes rocking to and fro in the distance.i

Lowndes was one of several pseudonyms adopted by a notorious highwayman, William Lewin (or Lewins). He also used the names William Henry Clarke, William Brown, Hutchinson, Maule and Hope. Born in about 1755 in Smallwood near Sandbach, William began his life as a weaver and a part-time dancing master. He was well-educated but restless. After an affair with a local girl, Betty Hayes, he was forced to marry her in 1775 and they had at least three children. However, in 1780 he abandoned his family and fled to Sunderland. Here, in 1782 he married Eliza Smith by whom he had a son, but again he abandoned the family and by 1785 was back in Derbyshire where he met Amy Clarke whom he also married bigamously. They lived in Chesterfield where they had two children and William resumed his career as a weaver, but the couple now embarked on a brief but dramatic five years of crime.

The focus of William's crimes was the Royal Mail. With the connivance of a post-boy he robbed the Mail in Congleton and then elsewhere in the north of the country. On 11 March 1788 he committed the offence that was eventually to be his downfall: he robbed the Warrington to Northwich Mail at Great Budworth, attacking James Archer, the post-boy with a pistol and a stake with a nail in the end of it. He fled with a horse and a considerable sum of money. The horse was retrieved but William escaped and spent some of the money on woollen cloth. Some of this was subsequently discovered in his house and a reward of £50 was offered for his arrest. A description read 'He is about thirty years of age, has very thick legs and thighs, close knee'd and is lame of his left thigh of a blow'ii

The family went on the run. William was spotted negotiating stolen bills in various places in the north and midlands of England and then the family fled to Ireland. Early in 1789 they returned to lodge in Beaumaris, Anglesey, and in June William was preparing another attack on the Mail in Cheshire. This was the one that inspired the remark by our Victorian walkers.

At midnight on the 29 June at Dunham on the Hill near Frodsham, William attacked and robbed the Frodsham post-boy, John Stanton.iii Our Victorian narrator had, in an earlier article, embellished this story somewhat, suggesting that the poor post-boy was tied to a tree and shot.iv This did not happen but in eighteenth-century England an attack on the Mail was regarded as a very serious crime indeed (akin, perhaps, to an attack on the Internet or On-line banking today). William had fled the one hundred miles back to Beaumaris, but the 'hue and cry' was up and his landlady in Beaumaris, Mrs Crow, grew suspicious and challenged him. He escaped her lodgings in the pouring rain and managed to cross to Carnarvon where, spotted at an inn, he leaped out of a window in his stockings and escaped into the mountains without his shoes. Amy followed from Beaumaris. Hiring a boat to Bangor, she paid the crew generously on arrival but the crew spent the money on getting drunk, which was not the best state in which to sail home. They are said to have drowned on their return across the Menai Straits.

By early 1790 Amy and William were reunited, living in Northumberland and then Darlington, continuing their life of crime. William was so successful at robbing the Mail, including an attack between Penrith and Keswick, that he became known as The Post Master. While the General Post Office raised the reward for his capture to £200 their advertisement described him as:

- about 35 or 36 years of age, five feet eight or nine inches high, stout made, of a dark complexion, has remarkable good black hair which he lately wore tied behind, has a florid complexion, large lips, is rather heavy limbed, and thick about the ankles... v

One reason for his success was that William was not limited to one particular place: he committed his crimes and cashed his stolen bills over a very wide area of the country. An excursion to London to cash stolen bills was followed by a journey as far as Exeter but here his career came to a halt. In Exeter William seems to have drawn attention to himself by entertaining extravagantly. He could afford to as on his death he is said to have left property worth upwards of £2000. On planning his exit from the City, he had invited local gentry to a grand farewell party but he met his nemesis in William Sorrell, Keeper of Exeter Castle Gaol. He was identified while playing skittles at the Plymouth Inn. When faced with arrest, William behaved with confident indignation, but Sorrell was not to be fooled. By September 1790 William was bound in irons and returning to face trial in Chester. He was displayed on the way by his captor at public identity parades in Oxford and in Derby.

Once in Chester Gaol and weighed down by leg-irons William, enthusiastically abetted by Amy, proceeded to plan an astonishing series of escape attempts. At first, Amy tried unsuccessfully to smuggle into the gaol two saws and a dozen files strapped to her thighs. Next, William engaged Amy, another prisoner and a corrupt turnkey in a complicated plan to take an impression of a key and have it smuggled out of the gaol to a locksmith in Wolverhampton. A third plan was for Amy to bring laudanum into the gaol to drug a turnkey. The turnkey subsequently died but no evidence was found to connect this to William. Another plan was for Amy to send in parcels of tea and sugar concealing a brace of pistols and ammunition. However, the servant girl, who was paid five shillings to do this, became suspicious of the weight of the parcels. A further mass escape of six prisoners, led by William, involved a direct attack on a turnkey who managed to throw his keys out of the window and raised the alarm as they climbed the wall:

- Lowndes...the mail-robber, seeing (the guards) coming, said to the other prisoners,'Come my lads, the plot's discover'd; come down again;' which they accordingly did and were all secured. The debtors are suspected of aiding the attempt: under one of their beds were found, a canvas bag, containing 42 guineas, and other articles, the property of Lowndes.vi

Another plan involved gunpowder but was foiled by an informant. All this sounds like scenes from a melodrama and certainly the newspaper reports may have been highly embroidered but, apart from reflecting on Amy's loyalty and William's tenacity, ingenuity and wealth, these episodes throw a very poor light on the state of security in Chester Gaol!

All escape plots having failed, William finally faced a trial at the assizes on 18 April 1791. There were four indictments for robbing mails but the offence for which he was actually tried was the 1788 attack on the post-boy at Great Budworth. Eight witnesses were called for the prosecution and evidence was heard for five hours. William called no witnesses and simply read out his own defence, declaring his innocence. He claimed that he had been prevented from calling witnesses and accused those who had identified him as doing it for money. On finding him guilty and the crime aggravated by his escape attempts, the judge, Edward Bearcroft, Chief Justice of Chester, sentenced William to death by hanging. Bearcroft, reflecting on the importance of the Mail, told him:

- You have been convicted upon as clear a chain of evidence as ever appeared in a court of justice, and of a crime so dreadful in its consequences that the legislature has very wisely thought fit to punish it with loss of life. For if it were otherwise, there would be an end to all commerce. The property of individuals, as well as of the public, must be protected.vii

He ruled that after execution the body was to be gibbeted. The prosecution was said to have cost more than £1500.

The execution was on Gallows Hill at Boughton, only three days after the trial, on 21 April 1791. There are accounts of William's gallows speech which follow a common pattern of the time with prayers and admonitions to the spectators, probably highly embellished by the reporters:

- as you regard your own souls , and eternal happiness , bring up your children to fear God , and keep his commandments , and then they will never be forsaken , or come to the shameful , ignominious end I am doomed to suffer ; learn them to shun evil , and do good... viii

William had asked Amy to attend and she came with one of his brothers. William handed her a letter and had expected her to publish an account of his life and conduct but she left Chester without giving any further information. He was standing in a horse-drawn cart with the noose around his neck. He gave a signal by dropping a handkerchief and the cart was drawn away to leave him hanging. It was reportedix that the executioner took a fancy to William's new black coat and demanded that the widow pay him a guinea for its return to her. The next day the body was displayed in a gibbet on Helsby Hill in sight of the place where William had robbed the Frodsham post-boy.

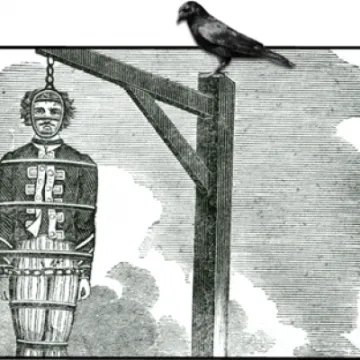

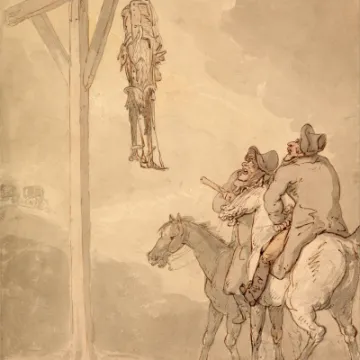

Gibbeting is not to be confused with execution. It was a post-execution punishment intended as a particularly graphic warning to other potential offenders. In the late eighteenth century, only a small percentage of executions were followed by a gibbeting which indicates how serious William's crimes were thought to be. The method varied between simply hanging the corpse in chains to enclosing it in a custom-made iron frame. It was suspended at a prominent location from a considerable height (although the 50 feet mentioned in this case seems excessive), and the ghastly sight (and smell) would surely have made an impression on all who passed nearby.

There are no contemporary accounts of what happened to the body after the gibbeting but a letter half a century later claims that...

- ...to prevent the body from being stolen by his friends, the upright baulk, 50 feet high, was thickly studded with iron spikes; and yet on the evening of the day that he attained so unenviable an elevation, his body was mysteriously taken away, how, or by whom, was never known. The gibbet irons were found some years after in a pit on the estate of Mr. Burgess, in the immediate neighbourhood. The socket hole of the gibbet is still visible on the rocky promontory of Helsby Hill.x

This was the same year in which our Victorian walkers heard of the story but the account they were given by the locals was somewhat different:

- Here his lifeless corse swung with the winds, a warning to all evil doers, who robbed the ... mails, until the farmers round about petitioned the authorities, and got the dangling body removed, for the wiseacres from Frodsham would not there buy their milk and butter, for old Lowndes tainted the neighbourhood. A blacksmith purchased the skullcap and fixing a handle thereto sold it to a dare-devil farmer, who used it for a broth-ladle.xi

The contradictions over the gory details and the embroidery of the events by the various reporters and chroniclers leave us with a rattling good yarn hanging by a tenuous thread of truth, and a lasting image of that gibbet, rocking on Helsby Hill, and of Lowndes, its notorious occupant.

SOURCES

- There are no contemporary records that can be considered to be wholly accurate. The most extensive of these is an anonymous pamphlet purporting to be an account of the trial together with the life and conduct of Lewin:

Anon 1791The Trial of William Lewin... Chester: Printed by J.Fletcher for J.Poole

- There were many contemporary newspaper reports which have been summarised in a helpful article by Leslie Phillips for the Chesterfield & District Family History Magazine (No.94, March 2013, pp14-17)

- In 1867, many years after the death of Lewin, a letter appeared in the Chester Chronicle which offered some further details. In the same year, two articles in the Ashton Weekly Reporter, and Stalybridge and Duckinfield Chronicle added information which seems to stem from folk memory about the attack near Frodsham.

- An account from a possible family descendant of Lowndes is available on-line:

- "The Trial of William Lewins", Warrington Public Library. 1759-1791" CLICK HERE

- Another modern account can be found in: Yarwood, Derek, 1991, Outrages – Fatal & Other: A Chronicle of Cheshire Crime 1612-1912. Manchester: Didsbury Press. Chapter 4 part 1.

PHOTOGRAPHS AND IMAGES

It seems probable that the gibbet socket was where the trig-point is today on Helsby Hill. However, just in front, closer to the cliff edge, there is a possible post hole that has been packed with stones. Could this have been the site of the gibbet? Other images represent 'gibbeting', the process whereby the corpse of an executed individual is used as a deterrent to other potential offenders (click on images to enlarge)

My thanks to Sue Lorimer, Helsby local historian and Sandstone Ridge Volunteer, for helping to sew this remarkable tale together.

Peter Winn, Trustee

iAshton Weekly Reporter, and Stalybridge and Duckinfield Chronicle, 6/4/1867

iiDerby Mercury, 29/5/1788.

iiiIdentified in a letter to the Chester Chronicle, 19 Jan 1867

ivAshton Weekly Reporter, and Stalybridge and Duckinfield Chronicle, 30/3/1867

vNewcastle Courant, 10/7/1790

viCaledonian Mercury, 14/2/1791. The debtors referred to were presumably other prisoners. According to a letter to the Chester Chronicle, 19 /1/ 1867, the irons worn by Lewin "were suspended against the wall of the criminal ward, and there was a tradition that, loaded with these heavy irons, he had sprung to the top of the wall some 8 or 10 feet high, and they were there suspended as a memento of the astounding feat."

viiThe Trial of William Lewin... p.14

viiiThe Trial of William Lewin... p.24

ixDerby Mercury 5/5/179)

xChester Chronicle 19/1/1867

xiAshton Weekly Reporter, and Stalybridge and Duckinfield Chronicle, 30/3/1867

Sandstone Ridge Trust

Registered Company No. 7673603

Registered Charity No. 1144470

info@sandstoneridge.org.uk