Bickerton Coppermine

Many people will be familiar with the chimney stack of Bickerton Coppermine, a distinctive landmark near the A534 on Gallantry Bank, but perhaps less familiar with its history.

See photo: Site of the copper mine in 2020

Copper mining in Cheshire has a long history, with evidence of Roman and Bronze Age mining activity at the Alderley Edge mines. Unfortunately, no evidence for these periods has been found at the Bickerton mine.

Copper ore occurs here within the Triassic Sandstone as a result of a whole series of particular geological processes and conditions. A key element is the large fault line running southwards down the eastern flank of the Peckforton Hills and at their southern margin, curving round westwards to extend to Gallantry Bank. A fault is a fracture in the earth's crust along which the rocks on either side have moved relative to each other. This movement is responsible for elevating the hard sandstones that now form the Ridge. Metal-rich fluids circulating at depth through the permeable sandstone became 'trapped' by impermeable rocks associated with this Peckforton Fault, eventually to precipitate out as copper mineral.

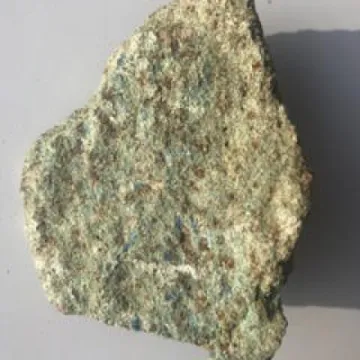

The copper itself typically occurs as malachite, disseminated through the host Triassic sandstone, having been deposited as a thin film around the sand grains or within spaces between the grains of sand. The photo of a rock specimen shows the general green colouration from the disseminated malachite, along with some blue patches of another copper mineral (either azurite or chrysocolla). In addition, brown spots of iron oxide can be seen.

See photo: Sample of copper ore

The earliest records of mining at Gallantry Bank date from the 1690s, during the reign of William and Mary, initially a little further east, in the area of woods just to the north of the Bickerton Poacher. These records include a letter written in 1697 by a mining engineer, J.D.Brandshagen, to the mine-owner, Sir Philip Egerton. In this he made many suggestions for the improvement of the workings and appended many Rules for running the mine. For a wage of 2 shillings a week, the miners were to be summoned to work by the sound of a hammer on an iron plate and at 6am, after a prayer, descend a shaft of little more than a metre wide. At 11am the plate was to be struck again for a surprisingly generous lunch break until 1pm when they were to go back into the mine until 6pm. Thus they were expected to spend ten hours underground – in winter slightly less. No'one was to smoke a pipe down below: this was not particularly dangerous but it wasted time and brought a fine of 4p for every pipe (one sixth of the weekly wage). Health and Safety was not a priority: the main obsessions of Brandshagen were discipline and economy and he made a particular point of ensuring that, should any of the iron picks and other tools be broken, the miners had to return all the pieces for re-casting or face a fine. Every miner also had to account for the candles he took down to give him light. Even the unused remains of candles had to be returned subject to a fine.

Brandshagen did, however, display some forward thinking in terms of Employee Relations: he accepted that workmen might be able to advise the Steward on some aspects of mining practice:

'Certain appointed times are to have a general review and thereupon a council of mines, with the most understanding workmans, that every one must give his sentiment about all things, which is to be drawn upon paper, out of which the Steward can see and ponder their meaning with his own, and conclude what to do best'.

He was also concerned about poor relief in the event of accidents but, rather than remind the employer of his duty of care, he preferred to encourage the workers to care for themselves:

... it often happened, that the miners and workmans get hurt, become sicke, dyed in poorness , left miserable creatures of wife and child ... by which the mines Lords are some time very much troubled to assist them. I have in some places found a remedy used for this, which has much pleased me, which is that every workmen must let a little part of his wages behind, as from 2 shillings but one farthing, of which the Steward must made a particular account, this will increase in short time to such a capital sufficient enough to help them in these miseries ...; they assist one an other without feeling the lost ... and the Lords of the mines are free from all these troubles ...

From these rules we can gain a picture of what the ideal conditions of working in a copper mine might have been in the seventeenth century. The fact that Brandshagen felt the need to propose them suggests that he found conditions at the mine somewhat worse. It is not clear whether Sir Philip took up any of these proposals.

In later years, mining moved westwards along the ore-zone, to where the chimney stack is located. This shaft, the Engine Shaft, was opened up sometime before 1807, with the Engine House, adjacent buildings and the familiar chimney being added in 1857. Mining at Bickerton largely ceased in the 1860's, although commercial interests continued into the early 20th Century. The mid 1850's was perhaps the most productive period for the Bickerton Mine.

See photo: The mine buildings circa 1906

The buildings seen in the photograph are reported to have been in a derelict state by 1886, (having been abandoned for some 20 years) and were finally dismantled in the 1920's. However, the OS (1:10,560) map of 1949 -1969 still shows the locations of the various mine buildings. The actual mine shaft was in-filled in 1977.

As well as the Engine Shaft at Gallantry Bank, a further 5 shafts have been recorded. These are located in private woodlands running eastwards along the fault line mentioned above, parallel and just north of the A534, towards the Bickerton Poacher. All that now remains of these workings are a few indistinct earthworks. An adit, or horizontal shaft, located below Bulkeley Hill still exists as a small, arched opening. This adit extends some 150ft north-eastwards into the hill. It was probably an exploratory trial, as opposed to a mine drainage tunnel, as it is topographically above the mine workings.

The engine house chimney, a few mounds of overgrown spoil and the fenced-off depression of the mine shaft is all that remains of the copper mining industry along the Sandstone Ridge.

More can be read about copper mining in Chris Carlon's 'The Gallantry Bank Copper Mine, Bickerton, Cheshire' in British Mining No.16, Northern Mine Research Society

Our thanks to Peter Winn and Nick Holmes for providing this article.

Sandstone Ridge Trust

Registered Company No. 7673603

Registered Charity No. 1144470

info@sandstoneridge.org.uk